Long gone are the days when false friends were simply duplicitous peers whose questionable understanding of friendship was detrimental to my long-term mental fitness and well-being. No, it’s much worse than that. As a translator, false friends are the linguistic speed bumps that can slow down both the creative and client hand-over processes. As an interpreter, however, false friends oscillate between speed bumps and a head-on collision.

All good translators and interpreters will not just be immersed in the language(s) they work with, they will understand and have a good feel for the nuanced cultural and idiosyncratic intricacies too. False friends (deceptive cognates/ faux amis) are generally known to good linguists and can be easily translated, without an embarrassing mistake.

For the non-induced, false friends can be funny or even embarrassing. Judging from the endless lists of false cognates that can be found online, there are abundant chances for unsuspecting language learners to push the wrong buttons or tickle some tummies while practising their newly learnt phrases.

To repeat some wonderful clangers, to be “embarazada” in Spanish is to be pregnant, and not embarrassed. A mist may be a light fog in English, it is the much-less romantic “poo” or “crap” in German. Confuse a “pickle” with a “Pickel” in German and you may end up eating someone’s facial goo rather than a yummy marinated cucumber. Taking (“cojer”) a bus in Spain can be fun, to use the same verb in Mexico, however, may land you in therapy (I’ll let you Google that one).

There are extensive writings on the exact definition of these false friends. It should come as no surprise that linguists have gaggles of definitions for the various permutations of false friends, their etymologies and impact.

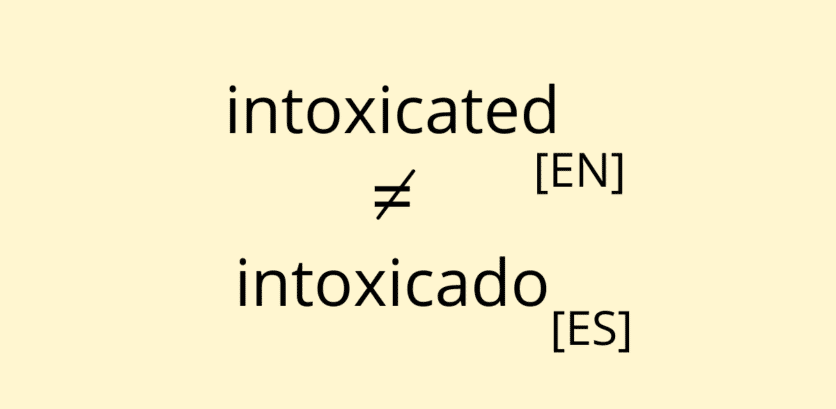

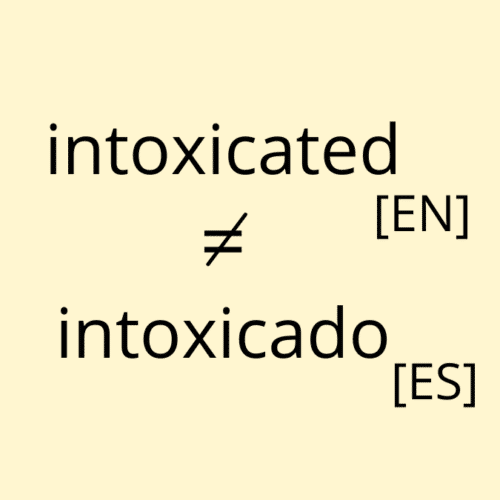

In 1980, the Spanish-speaking family of an unconscious 18-year-old Willie Ramirez rushed into the casualty department of a hospital and told the staff they feared he was “intoxicado”. The staff assumed they meant “intoxicated” and delayed treatment. They were trying to say he had been “poisoned”, “intoxicado” in Spanish does not carry the same negative implications as “intoxicated” in English. The doctors believed he was suffering from a self-induced overdose. He was actually experiencing a brain haemorrhage, the lack of immediate treatment left him quadriplegic. The mistake changed Willie Ramirez’s life forever and cost the hospital around $71 million in damages.

The embarrassment and dangers of false words or false phrases are the daily occupational hazards experienced by professional interpreters, who are required to pass over the faux pas of faux amis, without so much as a hiccup or smile. Among other issues, interpreters must flawlessly and simultaneously discuss nuclear arms deals, terrorism, border disputes and war, without hitting the wrong tone or phrase.

My thoughts and prayers go out to the interpreters today who have to convey Boris Johnson’s buffoonery, Vladimir Putin’s dry wit, Ramzan Kadyrov’s menace or Donald Trump’s spleen. That said, interpreters are obliged to transmit as much of the original speech as possible. So, the risk of accidentally embarrassing a whole country due to a bad choice of phrase or unwittingly setting off a war because of an errant adjective, is less dangerous when the original tone is ridiculous, obnoxious or bellicose to begin with.

Back in times of colder wars, Nikita Khrushchev remarked in a speech in Poland that communism would outlive capitalism, his interpreter had other plans. “We will bury you”, Khrushchev’s interpreter threatened. Strong words for a man with a huge nuclear arsenal at his fingertips, and almost certainly not the original intention.

When not in their booths at conferences, interpreters can be seen sitting between or behind world leaders, whispering in their ears or looking hungry at state banquets as they try to interpret and distinguish small talk from food noise.

A professional interpreter doesn’t just know false friends, they collect batches of standard clichés and phrases in both languages in order to avoid spur-of-the-moment interpretation – “We will bury you!”. It’s easy to find the lists but far more difficult to collect and practice the interpretation of phrases or proverbs from one language to another. False friends are actually the interpreter’s best friends, as knowledge of them can be the difference between exacerbating a war or simply lauding an economic theory.